D.C. Circuit: U.C.C. Article 4A Does Not Govern Judgment Creditors’ Claims to Sanctioned Company’s Funds Held by Intermediary Bank; Concurrence Calls for Clearer Standard.

On August 16, 2022, the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit issued its ruling in Estate of Jeremy Isadore Levine, et al. v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., No. 21-7036, –F.4th– (D.C. Circuit August 16, 2022), a case that required it to resolve competing claims to a blocked electronic funds transfer. On the one side was the United States, which blocked the transaction because terrorists initiated it. On the other side were victims of Iran-sponsored terrorism who have obtained multi-million dollar judgments against the Iranian government and who sought to attach these assets to satisfy their judgments (collectively referred to as the “Estates”).

Resolving these claims required the Court to first determine which law governed how a federal court should determine ownership of seized funds such that the assets could be attached by the Estates. In answering this question, the Court was tasked with determining whether the District Court erred in relying upon U.C.C. Article 4A § 4A-402—a state law—as a matter of federal common law, to determine whether Iran maintained a sufficient property interest in the blocked funds such that the Estate could attach them to collect their judgements against Iran under either § 201(a) of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act of 2022 (“TRIA”) or 28 U.S.C. § 1610(g) of the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act. (“FSIA”). In reversing the District Court, the D.C. Circuit explained that state law should only be adopted as the federal common law on an issue-by-issue basis with an analysis of whether that application would be consistent with the federal program at issue in the case.

The case is important in at least two respects. First, it helps clarify what law governs a determination of ownership of OFAC blocked funds for purposes of attachment by persons with judgments against terrorists, terrorist organizations, or state sponsors of terrorism. Second, the case provides a detailed analysis of the circumstances under which state law can be adopted as federal common law.

1. The electronic funds transfer, OFAC’s blocking action of funds wired through a U.S. intermediary bank, and the U.S.’s forfeiture action.

The electronic funds transfer at issue in the case stemmed from the attempted purchase of a Liberian registered oil tanker by Taif Mining Services, LLC, an Omani company. Importantly, because Taif Mining was formed by members of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the company is on OFAC’s Specifically Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons list. See Exec. Order No. 13, 224 (2001), as amended by Exec. Order No. 13,886 (2019); 31 C.F.R. § 594.201. Generally speaking, the SDN list is a list of individuals, groups, and entities whose assets are blocked and whom U.S. persons are generally prohibited from dealing with.

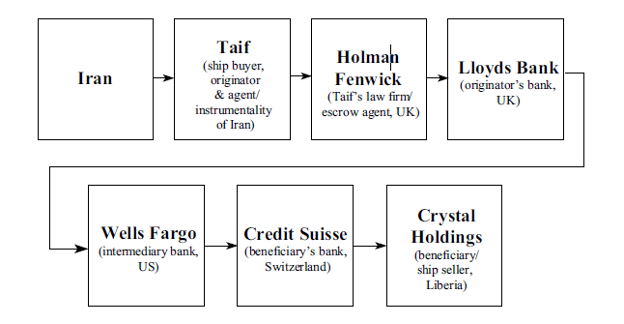

Taif Mining attempted to purchase the vessel in a two-part transaction with a London-based law firm, Holman Fenwick Willan LLP, serving as the escrow agent. The down payment of $2.34 million moved through the international banking system into the seller’s Credit Suisse Bank Swiss bank account. However, for the second payment, Taif Mining provided the escrow agent with $9.98 million dollars which the escrow agent held at Lloyds Bank PLC, in London. Taif Mining instructed the escrow agent to use an intermediary bank in the United States, Bank of New York

Mellon, to facilitate the transfer between Lloyds and Credit Suisse. (An intermediary bank is used in facilitating transactions when the transferor and transferee bank are not members of the same lending consortium. The intermediary bank is an establishment where both the transferor and transferee banks maintain accounts. When this occurs, the buyer’s money moves from the transferor bank to its account at the intermediary bank who then deposits that money in the transferee bank’s account who then pays seller.). Ultimately, Lloyds used Wells Fargo Bank as the intermediary.

For ease of reference, the Court included the following diagram:

However, due to Taif Mining’s involvement, the transaction was blocked upon Lloyd’s transfer to Wells Fargo, which then segregated the funds into a separate account it maintains for blocked funds. On May 1, 2020, the United States filed a forfeiture action for the blocked funds.

2. The Estates’ writs of attachment and the District Court’s quashing of the same.

Upon learning of the forfeiture action, the Estates’ filed writs of attachment seeking to attach the funds for satisfaction of judgements they had against Iran. The Estates sought the attachment pursuant to two statutes. The first, 28 U.S.C. § 1610(g) of the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act. (“FSIA”), subjects to attachment “the property of a foreign state . . . and the property of an agency or instrumentality of such a state” against which a plaintiff holds a judgment under 28 U.S.C. § 1605A. The second, § 201(a) of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act of 2022 (“TRIA”) (codified at 28 U.S.C. § 1610, “Satisfaction of Judgments from Blocked Assets of Terrorists, Terrorist Organizations, and State Sponsors of Terrorism”) subjects to execution or attachment “the blocked assets of [a] terrorist party (including the blocked assets of any agency or instrumentality of that terrorist party)”. Section 201(a) specifies that such assets can be attached “[n]otwithstanding any other provision of law.” The United States intervened and moved to quash the writs of attachment.

The District Court quashed the writs of attachment by ruling that Iran lacked any property interest in the blocked funds held by Wells Fargo. In so ruling, the District Court relied upon U.C.C. Article 4 § 4A-402 and the D.C. Circuit’s ruling in Heiser v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 735 F.3d 934 (D.C. Cir. 2013), which the District Court believed established 4A-402 as federal common law for the purpose of determining ownership interests in blocked funds in all cases.

In applying Article 4A, the District Court ruled that, even if it assumed that Taif Mining was the originator of the fund transfer, “the only entity with a property interest in an [electronic fund transfer] while it is midstream is the entity immediately preceding the bank ‘holding’ the [electronic funds transfer] in the transaction chain. In the context of a blocked transaction, this means that the only entity with a property interest in the stopped [electronic funds transfer] is the entity that passed the [electronic funds transfer] on to the bank where it presently rests.” Levin v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 523 F. Supp.3d 14, 21 (D.D.C. 2021). Based on this logic, the District Court found the only entity with a property interest in the blocked funds was Lloyd’s Bank—the transferor bank—not Taif Mining or Iran. Thus, because there was no Iranian property interest in the funds, the Estates could not attach them under either §201 or §1610(g) to collect their judgments.

3. The Circuit Court’s reversal.

a. The D.C. Circuit clarifies that U.C.C. § 4A-402 is not a universal principle of federal common law. Instead, state law is only incorporated into the federal common law on an issue-by-issue basis.

In reversing the District Court’s ruling that Lloyd’s Bank was the only entity with a property interest in the blocked funds, the D.C. Circuit examined whether U.C.C. Article 4 § 4A-402 applied at all and what, if any, significance its prior decision in Heiser should play in that analysis. The D.C. Circuit held that its decision in Heiser did not settle the issue of whether U.C.C. Article 4A would apply in all cases concerning ownership interests in blocked funds as a matter of “federal common law.” Estate of Jeremy Isadore Levine, at 11.

Instead, the Court held that “when federal courts incorporate state law as federal common law, such incorporation must be done as to a single issue at a time and the court must consider whether the issue’s outcome is consistent with the federal program.” Id. at 10. Thus, the D.C. Circuit concluded that Article 4A could be used to determine ownership of OFAC blocked funds “if and only if, on the issue presented, doing so would be consistent with TRIA § 201 and FSIA § 1610(g).” Id.

The Court noted that in Heiser, Article 4A’s application was consistent with TRIA § 201 and FSIA § 1610(g) because in that case the plaintiff attempted to attach a blocked electronic funds transfer at an intermediary bank whose end recipient was an Iranian bank. Id. at 9. The Court explained that in Heiser, the blocking foreclosed any claim that legal title had passed to Iran; therefore, because Congress did not “intend[ ] judgment creditors of foreign state to be able to attach property those states do not own[,]” applying Article 4A was consistent with the goal of TRIA § 201 and FSIA § 1610(g), i.e. to allow asset attachment while simultaneously protecting innocent third parties, which, in Heiser’s case, was the innocent third-party originator of funds. Id. at 9-10. As explained below, the Court found this analysis to be of limited application here where the originator of the electronic funds transfer was tied to Iran and therefore not an innocent third party.

b. 4A-402’s application would be inconsistent with TRIA § 201 and FSIA § 1610(g).

In determining that 4A-402 did not apply in this case, the Court compared the purposes behind U.C.C. Article 4A and OFAC’s regulatory scheme for blocking electronic funds transactions. The Court found that the purpose of Article 4A was to minimize disruptions in electronic funds transfers by creating a legal regime to “allocate risks and facilitate the unwinding of uncompleted fund transfers in a fair and orderly manner.” OFAC’s blocking scheme, on the other hand, is designed to disrupt terrorist electronic funds transfers and to prevent such unwinding. The D.C. Circuit explained that Commentary No. 16 of Article 4A notes that the Article’s principles “should not be ‘honored’” when an OFAC regulation disrupts an electronic fund transfer. Estate of Jeremy Isadore Levine, at 12-13

As a result of these differences, the Court found that the objectives of U.C.C. § 4A-402 and OFAC’s blocking regime were “incompatible.”

c. Ownership is governed by TRIA § 201. When that section is applied, the blocked funds were traceable to Iran such that the blocked assets could be attached.

Once it concluded that Article 4A did not apply, the D.C. Circuit next addressed which law governed whether the assets could be attached. The Court focused on TRIA § 201 which provides that blocked funds may be attached if those funds can be traced to a terrorist owner. However, such assets could only be attached “if no intermediate or upstream bank asserts an interest as an innocent third party.” Estate of Jeremy Isadore Levine, at 15. The Court explained that protecting innocent third parties is consistent with other situations under federal law, including forfeiture actions, in which tracing is employed.

Ultimately, when § 201 was applied, the Court found that the United States admitted that the blocked assets were traceable to Iran via Taif Mining and that neither Wells Fargo nor Lloyds asserted a claim to the funds. Thus, the D.C. Circuit concluded that the asserts were subject to attachment and reversed the ruling of the District Court.

d. Concurrence calls for adopting of agency principles to establish ownership under federal common law.

Judge Pillard issued a concurrence arguing that while she agreed with majority’s decision, she would have gone farther by explicitly hold that common-law ownership and agency principles apply instead of or in addition to tracing. According to Judge Pillard, tracing alone was insufficient to demonstrate that a terrorist party has “an ownership interest” in the funds sought to be attached, and that this ownership interest was a necessary component to attaching funds under TRIA § 201. As she further explained, the problem with relying solely on tracing is that “tracing presupposes ownership; it does not identify any legal rule for establishing ownership, or even require that ownership be shown.” Concurrence at 1. Thus, “the majority’s holding that the relevant funds may be attached so long as they are ‘traceable to Taif,’ stops short of specifying any rule of decision to substitute for U.C.C. Article 4A in proving the statutory required showing of ownership under Heiser.” Id.

To resolve the problem it identified, the concurrence advocated for the application of common-law ownership and agency principles. Under agency principles, banks effectuating electronic funds transfers would be viewed as agents of the terrorist-initiator rather than as owners of these terror-related originated funds as under Article 4A. The concurrence argued that treating banks as agents results in a conclusion that blocked funds belonged to the principal originator and would thus satisfy the twin aims of TRIA in both providing for attachment of funds owned by terrorist-related entities while still protecting innocent originators, such as the one at issue in Heiser. Concurrence at 3-4.

As applied in this case, the funds at issue would be attachable because Wells Fargo would be considered an agent of Taif Mining, and Taif Mining would be considered the principal and owner.

4. Conclusion

The Levin decision is not only important for those involved in FSIA and TRIA attachment proceedings, but also for anyone attempting to establish a principle of federal common law via the use of state law. In the D.C. Circuit’s initial application of U.C.C. Article 4A in Heiser, the Court noted that Article 4A was an appropriate rule of decision because it had been adopted as law in all fifty-states and D.C., and other provisions of the U.C.C. had previously served as a basis of federal common law. Heiser, 735 F.2d at 940. Thus, Heiser stands for the proposition that model state codes of widespread adoption may be appropriate sources to rely upon to establish open questions of federal common law.

However, Levin builds upon this analysis. Levin makes clear that state law should not be wholesale adopted as federal common law and instead must occur on an issue-by-issue basis after analyzing the purposes of the state law and the federal scheme at issue. Therefore, even if there is a model rule of widespread application at the state level, it still cannot be per se relied upon to establish federal common law if doing so would frustrate or be otherwise inconsistent with the relevant federal scheme.

In sum, when facing competing rules of ownership like the ones at issue in Levin, practitioners must be prepared to advocate not only why a state law should fill the void to create federal common law, but also why doing so will not be inconsistent with the purposes of the federal statute.

Regardless of which side you are on, FIDJ’s seasoned trial and appellate litigators can help you. For more information on how we can assist in your appellate or trial support needs, contact us at 305-350-5690 or info@fidjlaw.com